Page 107 - 4095-BOOK2

P. 107

It appears that part of that agreement allowed

for the bands to travel back to their former lands

at certain times of year for hunting. However, due

to a recent fight with the cattlemen who accused the bands of stealing

cattle, they had been told they were not allowed to return to their former

home. The bands, particularly the White River band, were angered and

appeared poised to force their way back to their hunting grounds. White

notes that this anger was compounded by rumors of U.S. troops on their

way to the reservations to enforce the government’s authority. It appears

that these rumors were primarily being spread by white settlers in the hopes

that the Indians would decide to fight the government, lose, and be killed

or removed from the land, though it was true that troops were en route. He

also states that the bands of the two reservations were primarily peaceful,

apart from the White River band, who just years earlier had taken part in the

Meeker Massacre of 1879, and generally stayed heavily armed and prepared

to fight at the drop of a hat.

After a brief meeting with some of the Uintah chiefs, White decided to call

a council of all the bands on the two reservations, hoping to extinguish

the anger before it erupted into violence. In his book, White notes the

uneasiness of the situation when the bands arrived the next morning,

stating, “The Uintah chiefs looked even more careworn and anxious than

they did the evening before. Many of their young men came with the

White Rivers, were heavily armed, and looked black and sullen. Among the

White Rivers pistols could be seen protruding from the folds of nearly every

blanket. Every belt was full of cartridges, and a Winchester rifle was slung to

every saddle. Sowawick, the principal chief, had two large revolvers buckled

on the outside of his blanket. They left all their ponies standing in a bunch,

and quite a large number of bucks remained with them and did not come in

to the council house at all — a most unusual circumstance.” He also says that

he had told all of his employees to stay within arms reach of their weapons,

but to appear calm and go about their daily business. White notes that he

took one other white man with him as an interpreter, James Davis, and said

that “I wanted the Indians to see that Davis and I were not afraid to go in

alone. Davis had one good pistol, and I gave him two more, and filled his

pockets full of cartridges. I also put two revolvers in my own pockets and

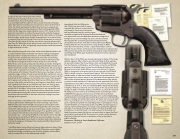

buckled two around me.”, one of which was almost certainly this revolver.

He says that upon entering the council, he removed the two pistols from

his pockets and tucked them in the front of his belt, sending a very clear

message to those present.

Upon entering the council, White notes that one of the first things he said

to those gathered was, “Washington has sent me among a great many

different tribes, but I never thought it necessary to carry weapons until I

saw the White Rivers ride up here this morning just like a war party. Then

I told all the white people to stay close by their guns outside; and when I

saw that Sowawick had left fifty of his young men to guard his ponies, and

was coming in here with those two pistols buckled around him — when I

saw all that I say — I armed myself with these four pistols, two for my right

hand and two for my left hand.” White then went on to address the room,

stating that Washington had no desire to take their land, before delivering

a bold and courageous challenge to the heavily army White Rivers band in

particular, saying:

“...the White Rivers look as if they had come to fight, and not to listen. If their

ears are closed against the truth I will not talk. If they have come to fight, I

want them to begin now while we are all in here together, because Davis

and I are ready, and so are the white people outside.”

Immediately after this, White notes

that, “All this was pure bluff, of course;

especially the reference to two pistols for

each hand, for I had never fired a pistol

with my left hand in my life, and was a poor

shot with my right hand.” His brave bluff worked however,

as it appears that even the White River band were indignant at

having been accused of seeking war, and a crisis was averted.

Not long after this council the government troops did arrive,

among them four troops of the famous African American “Buffalo

Soldiers”, who the Utes seemed to have a deep distrust of. White

notes that on the day they arrived, “...a great many Indians came to

talk with me about them, and many were the intimations in substance that

if they did not stay pretty close to their wickiups they would certainly ‘hear

something drop.’” White again handled the situation however, and peace

was maintained.

After his time in Utah, White was moved and placed in charge of the Osage

and Kaw agencies. After a time he was relieved of duty at those agencies.

He was sent to inspect the Ponca, Pawnee, Otoe and Oakland, the Sac and

Fox, the Cheyenne and Arapahoe, and the Kiowa, Comanche and Wichita

agencies. An included copy of a letter from the National Archives and

Records Service, which details White’s career, notes that on 21 February

1889, to assume duty as Inspector, which he was relieved of on 28 March

1889. He briefly served as a Special Agent Again in 1890, but it was not

until December of 1894 that he held another full-time position with the

Department of the Interior, when he was appointed assistant attorney in the

Office of the Assistant Attorney General for the Department of the Interior,

a position he held until March of 1896 when he was appointed Chief of the

Indian Division of the Office of the Secretary of the Interior, where he served

until February of 1900. In 1902, it is noted that White settled with his family

in Sulphur, Oklahoma, where he served as mayor, on the city council, and as

a judge. He died in 1908 after battling a brief illness, as a man who spent his

life trying to prevent violence by upholding justice and refusing to cower.

CONDITION: Very good as a historic treasure of the American frontier,

showing a weathered and aged brown patina, some scattered light pitting,

and the mild wear associated with a firearm that spent years in the American

West as a working gun and trusted sidearm. The grip is also very good with

some scattered minor dings and showing the wear of having spent time in

the sweating palm of a man poised to pull the trigger should he have to. It

remains mechanically excellent. The holster is fine, showing the mild wear

and signs of use typical of having spent time in the West. Even with clear

inscriptions, it is rare that firearms can truly be placed in the holster and

hand of a previous owner like this one can, particularly an owner that lived

such a historic and colorful life. This revolver is a treasure of the American

West, that could easily become a centerpiece of any such private or

public collection!

Provenance: The Brig & Louise Pemberton Collection.

Estimate: 10,000 - 20,000

105