Page 42 - 85-Book3

P. 42

bloody Bear Flag Revolt in California with Fremont. General Stephen W. Kearny employed him as

a guide in California during the Mexican-American War, and he helped save Kearny and his men when they came under attack near San Diego by sneaking through the enemy lines barefoot to get reinforcements.

After the war, Carson settled down as a rancher in New Mexico near Santa Fe but also continued to work as a government guide. It was during this period in his life that the rifle was presented. In early 1852, he made arrangements for a long hunt with his former trapper friends.

On March 17, 1852, the New York Daily Tribune ran a brief notice calculated to interest readers. It read: “The beaver trappers are again in motion. Kit Carson and Mr. Lucien Maxwell, his partner in business, are about starting out with a party of 40 to trap. There is not a doubt that they will bring in a great quantity of fur.” Kit Carson was the hook attracting attention to the announcement, since by this date his adventures in the West were widely known and admired. Notable also was the surprising reference to trappers being “again in motion.”

Back in 1840, the price of beaver fur had collapsed, just as Western streams and rivers were reported

40

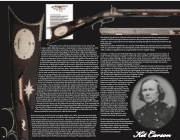

Christopher Carson, almost exclusively known to the world as Kit Carson, (1809-1868) likely needs no introduction to those interested in the 19th

century American frontier. He remains one of the most famous frontiersmen in American history and was a legend in his own time. Unlike many legends of the West, Carson wasn’t a mythical figure. He was the real deal. He actually did

survive an astounding number of skirmishes leaving many other men dead in his wake over many years in the early West, travelled vast swaths of the western half of North America from Oregon down to Chihuahua in Mexico, and was not prone

to telling tall tales about his exploits like so many other famous western figures. In fact, he was actually quite humble by all accounts. Aside from the fact that he just wasn’t the type, he didn’t need to; his life was incredible all on its own. He ran away

to the Santa Fe Trail just a few years after it opened when he was just 16 in 1826. The skill he advertised was that he could shoot straight. He joined up with trappers in

the fur trade seeking out beaver in unmapped stretches in the West just a few years later in the spring of 1829, and by the end of his life, he was the most famous of all of

the West’s trappers, scouts and Indian fighters. His activities were regularly featured in newspapers around the country. On his very first trapping expedition, when he

was but 19, he killed his first man, an Apache during an attack on the trappers’ camp. For the rest of his life, his relationship with Native Americans was complicated to put it very mildly as was so often the case with the trappers and frontiersmen of the era, but his actions as an Indian fighter and frontier guide made him a hero in the period.

Unlike many, he was not known to be an Indian hater and was well versed in tribal languages and with the differences between the various tribes living in the West. His

first marriage was preceded by a horseback duel with French trapper Joseph Chouinard, “the Bully of the Mountanins,” who was reportedly in love with Waanibe or Singing Grass,

a beautiful Arapaho woman that Carson loved as well. Per the stories, the Frenchman’s first shot grazed Carson’s face and cut a piece of his hair. Carson’s shot damaged the

trappers hand and blew off his thumb. It is unclear whether Carson finished him off with a second shot, but Carson won the battle and married Singing Grass. They reportedly had a devoted marriage, but it did not last long as she unfortunately died from complications

after the birth of their second daughter in 1841. While a trapper, he worked with many of the other legendary mountain men, including Jim Bridger, and attended some of the

famous rendezvous such as the one in 1839 at Horse Creek.

As the boom years of the fur trade era largely ended in the 1840s, Carson became nationally famous essentially by coincidence. He took his eldest daughter to Missouri to be raised by his sister and educated in St. Louis. He met John C. Fremont on a riverboat on the Missouri River at the beginning of the latter’s famous western expeditions and was hired on as a scout and guide as they explored, mapped, and claimed much of the West for the United States, often leaving Native American corpses in their wake. Fremont’s journals of their expeditions and

news reports led to Carson becoming a national hero, by some accounts without Carson himself even realizing it. Tales of Carson were also told in various articles and dime novels, which called him among other things the “Prince of the Gold Hunters” and “Prince of the Backwoodsmen.” Jessie Benton Fremont in “The Will and The Way Stories” wrote that, “Kit Carson is as well known [in the West] as the Duke is in Europe.” He also participated in the

to be trapped out. Mountain men like Carson and fur traders such as his friend Maxwell were forced into other lines of work. By 1852, both were developing ranch properties at Rayado on the east

side of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains from Taos. That spring, as Kit relates in his autobiography, “Mr. Maxwell and I rigged up a party to go trapping, I taking

charge of it.” In fact, the idea of a nostalgic trapping trip, as a sentimental journey into the past, seems to

have been entirely Kit’s. Veteran mountaineer Jim

Baker was one of those receiving an invitation

to join comrades on an old-time hunt. He accepted with glee. The message from Carson had said prophetically, “It will be our last.” Perhaps as many as 40 trappers had been originally invited, but the number as given in the Daily Tribune

has to be adjusted downward, for only 16 actually responded. So the final count, with the addition of Carson

and Maxwell, came to 18. Another, the Frenchman Alex Godey, however, was surely a member of the hearty band that rode out of Rayado headed north. With it were strings of pack mules bearing traps, skinning knives, camp equipment and kegs of gunpowder.

By this time, the beaver population had recovered thanks to a lack of hunting pressure that came with the decline in the fur trade in the 1840s. Carson, his business partner

Lucien Maxwell, Jim Baker, Alexis Godey,

and a party of around 14 other trappers set out from his farm at Rayado.

Kit Carson