Page 213 - 87-BOOK2

P. 213

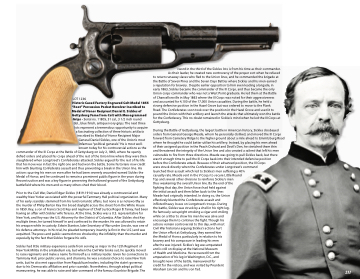

LOT 1236

Historic Cased Factory Engraved Colt Model 1855 “Root” Percussion Pocket Revolver Inscribed to Medal of Honor Recipient Daniel E. Sickles of Gettysburg Fame from Colt with Monogrammed

Grips - Serial no. 11805, 31 cal., 3 1/2 inch round bbl., blue finish, antique ivory grips. The next three

lots represent a tremendous opportunity to acquire a fascinating collection of three historic artifacts

inscribed to Medal of Honor Recipient Major General Daniel Sickles, one of the Union’s most

infamous “political generals.” He is most well- known today for his controversial actions as the

commander of the III Corps at the Battle of Gettysburg on July 2, 1863, where he openly defied orders and placed his corps ahead of the rest of the Union line where they were then slaughtered when Longstreet’s Confederates attacked. Sickles argued for the rest of his life that his move was in fact the right one and had won the battle. Some historians now credit him with blunting Confederate assault and thus preventing a break in the Union line. His actions spurring his men on even after he had been severely wounded earned Sickles the Medal of Honor, and he continued to remain a prominent public figure in the years during Reconstruction and was a key figure in preserving the hallowed ground of the Gettysburg battlefield where his men and so many others shed their blood.

Prior to the Civil War, Daniel Edgar Sickles (1819-1914) was already a controversial and wealthy New Yorker associated with the powerful Tammany Hall political organization. Many of his early scandals stemmed from his lurid romantic affairs, but none is as noteworthy as the murder of Philip Barton Key II in broad daylight across the street from the White House in 1859. Key, a son of Francis Scott Key and nephew of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, had been having an affair with Sickles’ wife Teressa. At the time, Sickles was a U.S. representative for New York, and Key was the U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia. After Sickles shot Key multiple times, he turned himself in and confessed to the murder. He was allowed to retain his weapon while in custody. Edwin Stanton, later Secretary of War under Lincoln, was one of his defense attorneys. In his trial, he pleaded temporary insanity (a first in the U.S.) and was acquitted. The press and public seemed more shocked by the infidelity than the murder and especially by the fact that Sickles forgave his wife.

Sickles had little military experience aside from serving as major in the 12th Regiment of New York Militia in the antebellum era, but when the Civil War broke out, he quickly moved to raise regiments and make a name for himself as a military leader. Given his connections to Tammany Hall, prior public service, and charisma, he was a natural choice to raise New York units, but he also met opposition from Republican leaders, including the state’s governor, due to his Democratic affiliation and prior scandals. Nonetheless, through adept political maneuvering, he was able to raise and take command of the famous Excelsior Brigade. The

sword in the third of the Sickles lots is from his time as their commander. As their leader, he created new controversy of the proper sort when he refused

to return runaway slaves who fled to the Union lines, and he commanded the brigade at the Battle of Seven Pines and the Seven Days Battles where Sickles and his men earned

a reputation for bravery. Despite earlier opposition to him even leading a brigade, in early 1863, Sickles became the commander of the III Corps, and thus became the only Union corps commander who was not a West Point graduate. He led them at the Battle

of Chancellorsville in May 1863 where the III Corps was noted for their aggressiveness and accounted for 4,100 of the 17,000 Union casualties. During the battle, he held a strong defensive position in the Hazel Grove but was ordered to move to the Plank

Road. The Confederates soon took over the position in the Hazel Grove and used it to pound the Union with their artillery and launch the attacks that ultimately won the battle for the Confederacy. This no doubt remained in Sickles’s mind when he led the III Corps at Gettysburg.

During the Battle of Gettysburg, the largest battle in American history, Sickles disobeyed orders from General George Meade, whom he personally disliked, and moved the III Corps forward from Cemetery Ridge to the higher ground about a mile ahead to Emmitsburg Road where he thought he could better utilize his artillery. Instead, by placing his men ahead

of their assigned position in the Peach Orchard and Devil’s Den, he stretched them thin and threatened the integrity of the Union line and also created a salient that left his men vulnerable to fire from three directions. Meade was going to pull Sickles back, but there wasn’t enough time to pull the III Corps back into their intended defensive position before the Confederate attack. Because of their advanced position, the III Corps

were struck directly when the Confederates under Longstreet’s command launched their assault which led to Sickles’s men suffering a 40%

casualty rate. Meade sent in the V Corps to secure Little Round

Top and several other divisions to reinforce Sickles’s men

thus weakening the overall Union line. By the end of the fighting that day, the Union forces had held against

the initial assault and then fallen back to the lines Meade had originally intended. In doing so, the Union effectively blunted the Confederate assault and

inflicted heavy losses on Longstreet’s troops. During the battle, Sickles was struck by a shell in his right leg. He famously sat upright smoking a cigar and smiling while on a litter to show his men he was alive and encourage them to continue the fight. Though his actions remain controversial to this day, with most Civil War historians arguing Sickles’s actions hurt

the Union effort at Gettysburg, they earned him the Medal of Honor, particularly in relation to his bravery and his composure in leading his men after he was injured. Sickles’s leg was amputated and is still on display at the National Museum

of Health and Medicine. He recovered from the amputation of his leg in Washington, D.C., and brought news of the battle, maneuvered for credit for the victory, and was visited by President Abraham Lincoln and his son Tad.

211