Page 84 - 87-BOOK2

P. 84

82

The death of Sitting Bull was a tragedy and was followed by one of the most infamous massacres in the history of the

American West. In 1890, he was nearly 60 years old. He famously was one

of the leaders of the Lakota at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, one of the most significant Native American victories in history, but, after the battle,

he and his followers fled to Canada in exile before returning to the U.S. impoverished and starving in 1881 and surrendering his Winchester carbine to the U.S. Army. He was held as a prisoner of war until the spring of 1883. In the mid-1880s Sitting Bull traveled the country as part of Wild West shows, including Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, and became a celebrity like other Native Americans before him such as Sauk leader Black Hawk who was taken on a tour of the East a half-century earlier under the orders of President Andrew Jackson. Showing Native American leaders the size and power of the U.S.

government by having them tour the great cities of the East was long part of U.S. efforts to end Native American resistance. When

Sitting Bull returned to the Standing Rock Agency, however, he was again in tension with government officials over conditions on the reservations and the selling of land. He advised his

people to resist having their land be taken yet again.

In 1890, the tensions that led to Sitting Bull’s death originated in part from what was originally a religious movement meant

to bring peace to the West: the Ghost Dance Movement started in 1889 by Wovoka, a Northern Paiute

spiritual leader in Nevada. Wovoka had called for peaceful relations between all people

under the Christian God and claimed that Jesus would return in 1892 and the living and the dead would be reunited. The people should live in peace and perform the Ghost Dance to ensure their eternal happiness.

As the movement spread, different peoples interpreted

the message differently. Many of the Lakota, for example, believed or

at least hoped that the Ghost Dance would ultimately rid the whites from their lands and bring back the buffalo

and other game that they had long relied on. Some believed that the whites would be washed

away from the continent in a great flood, earthquake,

and landslide.

This movement combined with government actions that imperiled the Lakota as a nation and their survival to create renewed hostility between the Lakota and the U.S. military. As was common throughout the 19th century, in early 1890, the U.S. government violated a treaty with the Lakota and began breaking up the Great Sioux Reservation into smaller reservations, attempting to force the Lakota to live on private holdings as families rather than tribes or bands, sending children away to boarding schools to strip them of their culture and teach them Euro-American ways in order

to assimilate the Lakota and ensure peace, and selling off “surplus”

Lakota land to white settlers. In addition to these injustices, the land

the Lakota lived on was not suited to farming which led to a food

crisis. Faced with further loss of their ancestral lands, starvation, and

the loss of their children, many Lakota were naturally drawn to the

Ghost Dance Movement which not only might provide a solution to

life in the present but also the salvation of their people for eternity.

Many government agents and settlers did not understand the Ghost Dance movement and feared that the Lakota were preparing for

war. In response, the U.S. Army was sent to the Lakota reservations

to attempt to force the Lakota to end the Ghost Dance. U.S. Indian Agent James McLaughlin stationed at Fort Yates sent the Indian Police, including relatives of Sitting Bull, to arrest the Hunkpapa Lakota leader to prevent him from leaving the reservation and potentially stirring

up a revolt. Lieutenant Henry Bullhead was ordered to arrest Sitting Bull quickly and quietly at dawn on December 15, 1890, before Sitting Bull could escape. 43 men, 39 of them Indian Police officers, arrived at Sitting Bull’s home between 5:30 and 6:00 a.m. Exactly what happened during the arrest varies from account to account.

It seems Sitting Bull was initially cooperative and considered

going away peaceably, but Hunkpapa Lakota men loyal to Sitting Bull were also alerted during the arrest and came to his aid. They did not initially attack until Sitting Bull began resisting arrest and was being forcibly removed by the police. Catch-the-Bear, one of Sitting Bull’s men, shot Lt. Bullhead with a rifle. Bullhead in turn shot Sitting Bull with a revolver before falling. A second officer, Red Tomahawk, also fired with a revolver hitting Sitting Bull again once or twice. Both Bullhead’s and Red Tomahawk’s shots would have been fatal by all accounts. Soon both sides were exchanging fire and fighting hand-to-hand. By the time Sitting Bull’s supporters fled, a total of eighteen men were killed. In addition to Bullhead who was shot multiple times and mortally wounded, seven other police officers were killed in the fight along with nine of Sitting Bull’s men, including one of his sons and one of his brothers,

slain by members of their own tribe in government uniforms. The remains of Sitting Bull, arguably the most famous Native American leader of the 19th century, were taken away and buried at Fort Yates.

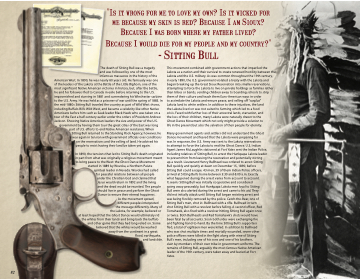

"Is it wrong for me to love my own? Is it wicked for me because my skin is red? Because I am Sioux? Because I was born where my father lived?

Because I would die for my people and my country?" - Sitting Bull