Page 208 - 88-BOOK2

P. 208

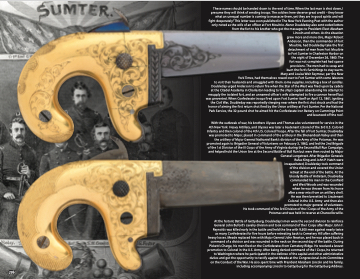

These names should be handed down to the end of time. When the last man is shot down, I presume they will think of sending troops. The soldiers here deserve great credit – they know what an unequal number is coming to massacre them, yet they are in good spirits and will fight desperately.” This letter was soon published in The New York Evening Post with the author only noted as the wife of an officer at Fort Moultrie. Abner Doubleday also sent coded letters from the fort to his brother who got the messages to President-Elect Abraham Lincoln and others. As the situation grew more and more dire, Major Robert Anderson, then the commander of Fort Moultrie, had Doubleday take the first detachment of men from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor on the night of December 26, 1860. The fort was not complete had had sparse provisions. The men had to scrap and burn the fort’s furnishings to stay warm. Mary and Louisa Weir Seymour, per the New York Times, had themselves rowed over to Fort Sumter with some laborers to visit their husbands and smuggled with them some supplies, including a box of candles. Doubleday urged Anderson to return fire when the Star of the West was fired upon by cadets at the Citadel Academy in Charleston leading to the ship’s captain abandoning his attempt to resupply the isolated fort, and an unnamed officer’s wife attempted to fire a cannon herself but was prevented. When Confederate troops fired upon Fort Sumter itself on April 12, 1861, igniting the Civil War, Doubleday was reportedly sleeping near where the first shot struck and had the honor of aiming the first return shot fired by the Union artillery at Fort Sumter. Per the National Park Service, the 32-pound shot he aimed hit the Confederate Iron Battery on Cummings Point and bounced off the roof.

With the outbreak of war, his brothers Ulysses and Thomas also volunteered for service in the 4th New York Heavy Artillery, and Ulysses was later a lieutenant colonel of the 3rd U.S. Colored Infantry and then colonel of the 4th U.S. Colored Troops. After the fall of Fort Sumter, Doubleday was promoted to Major, placed in command of the artillery in the Shenandoah Valley and then the artillery of Major General Nathaniel Bank’s division of the Army of the Potomac. He was promoted again to Brigadier General of Volunteers on February 3, 1862, and led the 2nd Brigade of the 1st Division of the III Corps of the Army of Virginia during the Second Bull Run Campaign, and helped hold the Union line at the Second Battle of Bull Run but were then routed by Major General Longstreet. After Brigadier Generals Rufus King and John P. Hatch were incapacitated, Doubleday took command of the division and covered the Union retreat at the end of the battle. At the bloody Battle of Antietam, Doubleday commanded his men in the Cornfield and West Woods and was wounded when he was thrown from his horse after a near miss from an artillery shell. He was then brevetted to Lieutenant Colonel in the U.S. Army and then also promoted to major general of volunteers. He took command of the 3rd Division of the I Corps of the Army of the Potomac and was held in reserve at Chancellorsville.

At the historic Battle of Gettysburg, Doubleday’s men were the second division to reinforce

General John Buford’s cavalry division and took command of the I Corps after Major John F. Reynolds was killed early in the battle and held the line with 9,500 men against nearly twice as many Confederates for five hours before retreating back to Cemetery Hill after suffering heavy losses. Meade replaced him with Major General John Newton, and he was placed back in command of a division and was wounded in the neck on the second day of the battle. During Pickett’s Charge, his men fired on the Confederates from Cemetery Ridge. He received a brevet promotion to Colonel in the U.S. Army. After being denied command of the I Corps, he returned to Washington where he participated in the defense of the capital and other administrative duties and got the opportunity to testify against Meade at the Congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. He also spent time with President Abraham Lincoln and his family, including accompanying Lincoln to Gettysburg for the Gettysburg Address.

206