Page 140 - 86-Book2

P. 140

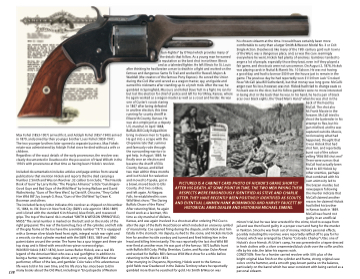

PICTURED IS A CABINET CARD PHOTO OF HICKOK’S GRAVE SHORTLY AFTER HIS DEATH. AT SOME POINT IN TIME, THE TWO MEN PAYING THEIR RESPECTS WERE ERRONEOUSLY IDENTIFIED AS STEVE AND CHARLIE UTTER. THEY HAVE RECENTLY BEEN POSITIVELY IDENTIFIED AS SCOUTS AND EVENTUAL LAWMEN HANK WORMWOOD AND HARVEY FAUCETT BY HISTORICAL ARMS DEALER AND HISTORIAN MICHAEL SIMENS.

138

Max Fishel (1853-1907) arrived first, and Adolph Fishel (1857-1940) arrived in 1879, and joined by their younger brother Louis Fishel (1859-1941).

The two younger brothers later opened a separate business. Max Fishels estate was administered by Adolph Fishel since he died without a wife or children.

Regardless of the exact details of the early provenance, the revolver was clearly documented in Deadwood in the possession of Hazel Willoth in the 1930’s with provenance at that time as having been Hickok’s revolver.

Included documentation includes articles and page entries from several publications that mention Hickok and reports that he died carrying a Number 2 Smith and Wesson Revolver .32 caliber to include; “The Fireside Book of Guns” by Larry Koller, “The Peoples Almanac” article “Gunslingers- Good Guys and Bad Guys of the Wild West” by Irving Wallace and David Wallechinsky, “Guns of The New West”, by David R. Chicoine, “They Called Him Wild Bill”, by Joseph G. Rosa, “Guns of the Old West” by Dean K. Boorman and others.

The included factory letter indicates this revolver as shipped on November 15, 1864, to J.W. Storrs in New York City (S&W’s sole agent in 1856-1869) and is listed with the standard 6 inch barrel, blue finish, and rosewood grips. The top of the barrel rib is marked “SMITH & WESSON SPRINGFIELD, MASS.” The serial number is marked on the butt and on the inside of the right grip panel. The rear of the barrel lug, face of the cylinder, and left side of the grip frame at the toe have the assembly number “19.” It is equipped with a German silver blade fixed front sight, integral notch rear sight and

a smooth, six-shot cylinder marked with the S&W 1855, 1859 and 1860 patent dates around the center. The frame has a spur trigger and three-pin top strap and is fitted with smooth two-piece rosewood grips.

Wild Bill Hickok (1837-1876), born James Butler Hickok, was a real life legend of the American West who was a real gunfighter in addition to being a hunter, teamster, stage driver, army scout, spy, Wild West show performer, officer of the law, and gambler. Color tales of his adventurous life were told in his own time, and his life story has since been told in many books about the Old West, including in “Encyclopedia of Western

Gun-Fighter” by O’Neal which provides many of the details that follow. As a young man he earned

a reputation as the best shot in northern Illinois and as a talented fighter. He left Illinois for St. Louis after thinking he had beaten a man to death in a fight and worked on the

famous and dangerous Sante Fe Trail and worked for Russell, Majors & Waddell (the creators of the famous Pony Express). He served the Union during the Civil War and served as a wagon master, spy, and guide and earned his nickname after standing up to a lynch mob. After the war, he gambled in Springfield, Missouri, and killed Dave Tutt in a fight. He ran for but lost the election for chief of police and left for Fort Riley, Kansas, where he again worked as a wagon-master as well as a scout and herder. He was one of Custer’s scouts staring

in 1867 after being defeated

in another election, this time running for county sheriff in Ellsworth County, Kansas. He was also employed as a deputy U.S. marshal. In April 1868, Buffalo Bill Cody helped him bring in eleven men to Topeka. He got into a scrape with the Cheyenne late that summer and famously rode through the surrounding warriors to get help. In August 1869, he finally won an election and became the sheriff of Ellis County, Kansas, and killed

two men within three months

and lost his bid for reelection

and moved to Topeka, got in

a brawl, moved back to Ellis

County, shot two soldiers,

and left again. At Niagara

Falls, he established his own

Wild West show: “The Daring

Buffalo Chase of the Plains.”

After returning West, he again

found work as a lawman, this

time as city marshal of Abilene,

Kansas, and was again involved in a shootout after ordering Phil Coe to alter the sign of the Bull’s Head Saloon which included an unsavory symbol of masculinity. Coe opened firing during the dispute, and Hickok shot him fatally in the stomach. His deputy, rushed to the scene, and Hickok mistook him for another hostile cowboy and turned and fired hitting him in the head and killing him instantly. This was reportedly the last shot Wild Bill ever fired at another man. He was part of the famous 1872 buffalo hunt with Buffalo Bill Cody, Phillip Sheridan, Custer, and Russian Duke Alexei and worked for Buffalo Bill’s famous Wild West show for a while before returning to the West in 1874.

After marrying in Cheyenne, Wyoming, Hickok went to the famous gold fields near Deadwood in the Dakota Territory where he reportedly gambled more than he searched for gold. His Smith & Wesson was

his chosen sidearm at the time. It would have certainly been more comfortable to carry than a larger Smith & Wesson Model No. 3 or Colt Single Action. Deadwood, like many of the 19th century gold rush towns of the West, was a dangerous place, and, as was the case seemingly everywhere he went, Hickok had plenty of enemies. Gamblers tended to anger a lot of people, especially those they beat, even in if they played a fair game, and shootouts were not uncommon. On August 2, 1876, Hickok was playing cards in Nuttal & Mann’s No. 10 Saloon. He was not having

a good day, and had to borrow $50 from the house just to remain in the game. The previous day he had reportedly won $110 from Jack “Crooked Nose” McCall (aka Bill Sutherland), but that money was long gone. McCall’s anger over his loss, however, was not. Hickok had tried to change seats so his back was to the door, but his fellow gamblers were no more interested in being shot in the back than he was. In his hand, he had a pair of black aces over black eights, the “Dead Man’s Hand,” when he was shot in the

back of the head by McCall. The shot also

hit Frank Massie in the forearm. McCall tried to shoot the bartender in his attempt to flee, but his gun misfired, and he was captured outside. Massie, not knowing what had happened, thought that

it was Hickok that had shot him, and reportedly burst out of the saloon yelling “Wild Bill shot me!” There were rumors that McCall had actually been hired to kill Hickok by other enemies, perhaps that combined with his own animosity led to

the brazen murder, but newspapers following

the murder indicate that McCall claimed another reason: he claimed Hickok had killed his brother

in Kansas back in 1869. McCall was found not guilty in an unofficial

miners’ trial, but he was later arrested for the crime, tried to escape from jail and was then found guilty in a proper court and hung for the murder

in Yankton. Since he was fresh out of money, Hickok’s personal effects, possibly including this revolver, were reportedly raffled off to pay for his funeral, which was arranged by Charles “Colorado Charley” Utter, one of Hickok’s close friends. At Utter’s camp, he was presented in a tepee dressed in fresh clothes with a silver ornamented black cloth over the coffin and his rifle by his side, the latter his express wish.

CONDITION: Fine for a frontier carried revolver with 50% plus of the

bright original blue finish on the cylinder and frame, strong original case colors on the hammer, and a smooth gray-brown patina on the balance, particularly on the barrel which has wear consistent with being carried as a personal sidearm.